Want to receive news on upcoming projects and events?

Watch the Grow with Sophia's Series

Interviews-Media-Speeches

Learn more

Articles

Learn moreDonate to Sophia's Voice

You can follow our journey here

TIKTOK: @NatalieCWeaver

Twitter: @NatalieCweaver

Instagram: @NatalieCWeaver

Facebook:

@NatalieWeaverAdvocacy

Youtube: @NatalieWeaverSweetSophia

About Natalie Weaver

As her online presence grew, Natalie began receiving hateful messages about Sophia's appearance and life. This inspired Weaver to take action against social media platforms to do more to protect users with disabilities and facial differences. She has worked with Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. Natalie’s story has been featured in media outlets like People Magazine, CNN and The Today Show, bringing national attention to the issues facing people with facial differences and disabilities.

Natalie continues this important work in memory of her daughter Sophia, who passed away in 2019, to keep her impact on this world alive. Natalie's advocacy is driven by her love for Sophia and her desire to make the world a more just place for all people, regardless of their abilities and the way they look. Her story and Sophia's journey have inspired many and highlighted the importance of fighting discrimination in all forms. Her work reminds us that small acts of speaking up can make a big difference, one human being at a time. As Natalie continues sharing Sophia's story, she hopes to spread a message of compassion and inclusion. Together, we can build a world where disability is accepted, accommodated, and celebrated as just another part of our shared human diversity.

If you haven't heard the term ableism before, I can give you the simplified version. Ableism is the belief that non-disabled people are better than disabled people. It implies that able bodies are the standard to go by, and these beliefs create an inaccessible, dangerous and unaccepting world. There is much more to it, and you can find detailed articles on this matter written by disabled people. We must start listening to disabled activists because their work is vital to us. I know I am better for it, and more importantly, I was a better mother to Sophia because of it. I had my ableism to unlearn, as do most people. It didn't take long after my child's death for people to start erasing the disabilities and facial differences that made Sophia, Sophia. I was bombarded with "well-meaning" wishes wrapped in horrible ableism. I heard awful things like: "You should find happiness knowing she is normal now." "You should feel relief that she is no longer a burden to you and your family." "You can smile now, knowing she looks normal now." "You should be grateful because her disabilities are gone." "You are a selfish mother for wishing she was here with you because she's in a better place" These are just a few examples of the many messages I received after my child's death. These types of examples of ableism are the very harmful belief that disabled people are better off dead. Can you imagine being told this about the death of someone you love? Probably not. Yet, somehow these types of comments were acceptable in some people's eyes because my child was disabled. When I asked people to stop saying hurtful things about my child, I was called ungrateful and worse because, after all, they were just trying to help. I noticed that nothing angered or turned people against me more quickly than expressing that their "well-meaning" comments about my child's death were harmful to me. We should want to do better when we know better, especially when trying to support grieving parents, but that wasn't the case. Their responses were filled with anger and hate. Were people becoming angry because they were told they aren't helping or because they hold so tightly to their beliefs that disability is bad and that death is better than having a disability? I've spent long enough advocating for Sophia and working to normalize facial differences and profound disabilities to know the answer. Unfortunately, in most cases, it is the latter. I experienced this type of anger long before Sophia's death. However, it was incomprehensible to me that even after my child's death, I was still fighting for her right to exist, to be loved as she was, and for my right to feel devastated and grieve her death because she was disabled. Not only was I dealing with the death of my child, now people were trying to erase the disabilities and facial differences that were a part of what made her my Sweet Sophia. I had to read beliefs like this and the everyday harmful comments people tell bereaved parents when they express their deep pain. People like to remind us that we have other children to think about as if we've somehow forgotten or that it's time to move on as if the death of our child is something we will ever get over. The lack of understanding, unsolicited opinions, and advice was overwhelming. I understand that some parents find relief in believing their child's disabilities have disappeared after their death, but not all parents feel that way. I am one of those parents, and I know many others who feel the same. To erase our child's disabilities after their death is to erase parts of them that made them who they were. My child's disabilities and facial differences are a part of what made her who she was and why she was so damn impressive. When I picture my child now, I see her rolling around freely in her cool neon green wheelchair we picked out together. I see her beautifully unique face, and I see her speaking to me with her beautiful and expressive eyes. That's what comforts me. I don't erase Sophia's disabilities and facial differences because doing that erases the parts that made her who she was. We loved all of who she was, her personality, disabilities, facial differences, and all. If you must say something, you can say that Sophia is free of the medical conditions that caused her pain and free of the conditions that led to her death. If God and heaven are what you believe in, you can tell me heaven is fully accessible. Tell me her differences are celebrated. Tell me that everyone there can see her soul, read her expressive eyes, and that no words are needed to understand her. Tell me she experiences nothing but love, kindness, and acceptance. The reality of child loss is that nothing you say will make us feel better or take away our pain. The best way to support a grieving parent is to allow us to feel and express our heart-shattering pain. Bring up our child, sit with us in our pain, and acknowledge how bad it is. Don't try to bright side us because there is no bright side to losing a child, disabled or not. You or someone close to you will be touched by disability at some point in your life. Disability is a natural part of life. It's way past time that we unlearn ableist behaviors toward disabled people in life and death.

I was struggling, but the struggle is beginning to lift. I was struggling because I was reliving the feelings of isolation we experienced to keep Sophia safe, but this time it was without Sophia. I was struggling because every time my heart dropped due to my reflex to protect Sophia, I had to remind myself that Sophia was safe now, which meant she is no longer here. I was struggling because all of this was triggering my medical-related PTSD, trauma, and past fears I felt for over a decade of Sophia's life. I was struggling because I realized that a majority of my grief/mental health supports and routines were found outside of my home, which I can't do during this time. I was struggling because it's the longest I had felt okay since Sophia's death, and now my grief felt heavy again. I was struggling because I once again had to readjust my life when I had gotten myself in a good place. I was struggling because I was hiding again and didn't feel I could be myself in a world that wants me to be pleasant, positive and moving on from my grief and pain. I was struggling, but the struggle is beginning to lift. Once again, I'm finding a new normal that involves me being gentle with myself and accepting of ALL of my feelings. I'm no longer resisting. I just needed time to readjust. I'm reminded of the many things I have to be grateful for, which includes being alive and more quality time with my kids and husband. Today, I’m recommitting to finding a good routine for my grief and mental health at home. It will take time but I will find my place again. I’ve done it many times in my life and I will do it again. Please don't forget to check on your friends that were already going through challenging times. Ask them how they are REALLY doing. Make them feel safe to be themselves. It makes a huge difference. Grief never truly leaves us. #SweetSophia #MentalHealth #MedicalPtsd #Grief #GriefJourney #ChildLoss #Anxiety

I acquired this ability out of necessity to protect my physical and mental health while recovering from the trauma of losing my child. I've experienced many hurtful things throughout this time, like people sending me messages(which is why I don't check them as much) celebrating my daughter's death and other cruel and selfish behaviors. Earlier on, as each hurtful situation was thrown at me, I could feel the pressure on my heart increasing. As the physical pain in my chest got worse, I suddenly realized that I couldn't go down this unhealthy path. I've been through more than enough. My heart, mind, and soul are already filled with the worst pain of my life. I have no more space in my heart for people that want to add to my pain. Besides, none of this other stuff matters anymore, not like it used to. I decided to no longer carry the hurt caused by others, past, present, or future. I let it all go and continue to move forward. I've been practicing this for the last six months or so. It's gotten more natural to do as time goes on, and it has made a positive difference in my life. As with most things, I'll always have to work on this and I hope I can keep it up! Now, I try to focus on working through my grief, being kind and forgiving to myself and others, being there for my beautiful family, spending time with them, and honoring Sophia by keeping her story alive and by appreciating life as much as possible. I keep my attention on the kind, compassionate, and supportive people, and there are a lot of you! #SweetSophia #ChildLoss #Grief #Reflection #MentalHealth

Almost. F**k you Almost. I almost got that book deal. I almost got that tv show/documentary. I almost made it on that huge talk show. I almost followed through on that great idea. I almost got mainstream media to pay attention. I almost had considerable opportunities to change the world, open millions of eyes to true beauty, unconditional love, acceptance, and to normalize profound disabilities and complex facial differences. Almost but not quite. Why? Why couldn't I make it happen? Why wasn't my cause important enough? Why wasn't I good enough, strong enough, bold enough, interesting enough? When I focus on the opportunities that almost happened, it makes me feel like I've failed and that I didn't fight hard enough. I wanted nothing more than to change the world and make it a better and more accepting place for Sophia while she was here, but I didn't have enough time. If I had started sooner and not allowed my fear and the horrible treatment and reactions of others to destroy me, then maybe I could've done a lot more and accomplished that dream while Sophia was here. If I allow myself to go down the path of almosts, then I feel like I should quit, but I can't. I promised Sophia before she died that I wouldn't abandon the vital work we started together. So instead, I will focus on the things I did, the opportunities I had, and the changes we made. I will think about the lives we've changed, and the eyes and hearts we've opened. I will think about the pride in Sophia's face when I shared the impact she was having on this world. We did a lot in three years and accomplished more than I could've ever imagined, and I will continue to focus on that. Even though my beautiful Sophia is no longer here to experience or see the change I fought so hard for, I will still fight to make this world a better, kinder and more accepting place for her and people like her. The thought of the opportunities I almost had but didn't, won't make me quit, and they won't make me feel as though I am not good enough. So, f**k you Almost.

Forgive Yourself Forgive yourself for not just being a mom but also needing to be a nurse, doctor, specialist, therapist, researcher, employer, advocate, and more. You did it so your child could have the best life possible. Forgive yourself for ignoring the mounting stress, fear, and pain you carried about someday losing your child. You did it to get through every day without crumbling. Forgive yourself for not realizing others felt the stress that you tried so hard to hide. You became so comfortable with the pressure that you sometimes didn't notice it was there. Forgive yourself for being on edge and anxious. You were waiting and listening for 'the' call, alarms, or signs of distress so you could drop everything to save your child and keep them alive. Forgive yourself for not taking care of your mind and body like you should’ve and paying for it now. You were under massive amounts of stress. Forgive yourself for not being all the things you wanted to be for all the people you love. You were dealing with unbelievable circumstances and couldn't be strong forever. Forgive yourself for making mistakes. You are not perfect, and no one but you expects you to be. Forgive yourself for breaking down. You held it together for so long and had to break to rebuild. Forgive yourself for not being able to save your child or take away their pain. You did everything you possibly could to keep your child safe, happy, loved, and alive. Forgive yourself. #SweetSophia #Grief #ChildLoss

Grief can be a very lonely journey, but I don't think it has to be. You can’t walk this path for me, but you can walk alongside me to remind me I’m not alone. This journey is teaching me to let more people in, and my life is better because of it. It's not easy for me, a natural loner, but it is necessary. We need people, no matter how strong and independent we are. It’s better to ask for what you need instead of walking this path alone. I’m still working on this myself. Fear of being a burden, being hurt, or disappointed sometimes holds me back, but I realize it’s better to know who is willing to be there and who is not. You might be surprised by the number of people that are willing to be there if you let them. Also, whether or not someone can be there for you does not make them good or bad, right or wrong. Everyone is different, going through things and have different capacities at different times in their lives. Realizing and accepting this has helped me and kept my heart more open. I'm forever grateful for the community I have because of my powerful Sophia. My friend Dianne Gray called her ’the connector’ and I do believe she continues to connect me to others just when I need it. It's been magical to experience these beautiful moments. I read these today, which is what got me thinking and inspired my above thoughts. I'm sharing in case it might help someone else. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ I read these today which is what got me thinking and inspired my above thoughts. I'm sharing in case it might help someone else. “𝘛𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘸𝘩𝘰 𝘸𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘵 𝘶𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘦 𝘸𝘢𝘵𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘦𝘺𝘦𝘴, 𝘢𝘸𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘥. 𝘕𝘰 𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘬𝘯𝘰𝘸 𝘩𝘰𝘸 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘦𝘭𝘱 𝘶𝘯𝘭𝘦𝘴𝘴 𝘸𝘦 𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘤𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮. 𝘌𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘺𝘰𝘯𝘦 𝘪𝘴 𝘴𝘰 𝘶𝘯𝘯𝘦𝘳𝘷𝘦𝘥 𝘣𝘺 𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘩 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘺 𝘧𝘦𝘦𝘭 𝘪𝘯𝘢𝘥𝘦𝘲𝘶𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘱𝘢𝘪𝘯 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘴𝘦 𝘪𝘵 𝘩𝘢𝘴 𝘳𝘰𝘣𝘣𝘦𝘥.” -𝘉𝘢𝘳𝘣𝘢𝘳𝘢 𝘓𝘢𝘻𝘦𝘢𝘳 𝘈𝘴𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘳 “𝘐𝘵 𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘱𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘱𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘵𝘦 𝘵𝘰 𝘵𝘦𝘭𝘭 𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘮 𝘸𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥. 𝘐 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴 𝘢 𝘭𝘰𝘵 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘐 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘪𝘥𝘦𝘢𝘴 𝘰𝘳 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘮𝘱𝘵𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘦𝘳 𝘮𝘦 𝘶𝘱. 𝘐 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘱𝘳𝘦𝘴𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘐 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘢𝘥𝘷𝘪𝘤𝘦. 𝘐𝘧 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘫𝘶𝘴𝘵 𝘣𝘦 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘵𝘢𝘣𝘭𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘮𝘺 𝘵𝘦𝘢𝘳𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘴𝘪𝘭𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦, 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯 𝘣𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘮𝘰𝘴𝘵 𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘥𝘦𝘳𝘧𝘶𝘭 𝘧𝘳𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘥 𝘪𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘸𝘰𝘳𝘭𝘥.” 𝘋𝘰𝘶𝘨 𝘔𝘢𝘯𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 #ChildLoss #Grief #SweetSophia

I’m laying in bed today. Not all day, but for a little bit. This is a big step for me. I went to grief counseling yesterday, and I talked about my extreme discomfort with fully relaxing while at home. So, this is my new assignment. Get comfortable with doing nothing and something mindless. I'm about to watch tv during the day. For the ten and a half years of Sophia’s life, I was always on high alert. I was always waiting and ready for the moment I’d have to drop everything to perform medical interventions. This happened almost daily. She did have calm weeks and months, but my anxiety was always present, just in case, and I had adjusted to this. Yesterday, I told my therapist that I was ready to face the traumas of watching my child in many life-threatening situations, performing emergency medical tasks at the drop of a dime, and watching my child take her last breath. I don't know how to do that yet, but I'm ready to learn. We think of people in the military when we speak of PTSD, but many other people experience it too. Parents of kids with life-limiting and chronic illness face it as well. Some triggers send me into panic mode, like beeps, coughing, sirens, choking sounds, running errands, and not being able to find things. All relate back to life-threatening situations. I could be in panic mode, and you might not even know it unless you know me. I got good at hiding it. I had to go about life, pick my kids up from school, be a mom, wife, and advocate. So I stuffed it down, ignored it, and kept going. My body still carries the memories, and it hasn't adjusted to her being gone. I'm going to try a new therapy for PTSD called EMDR. I want to learn to face my traumas and live without these triggers. I'm tired all the damn time, and my memory has been horrible for years. I'm hoping that this will all improve one day. Have any of you tried this therapy, and has it helped? Have you been able to move beyond the triggers that were caused by your traumas? #SweetSophia #ChildLoss #Grief #Trauma #PTSD #MentalHealth

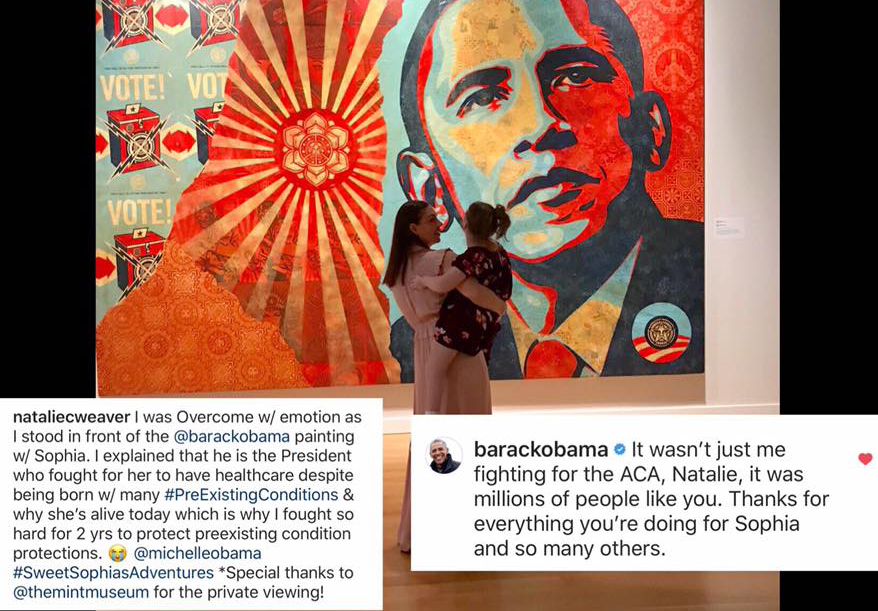

To sit in a moment that your child created even though she is no longer here is such a powerful thing. One of Sophia's adventures was a private tour of @themintmuseum thanks to Michelle Boudin & Caroline. Sophia loved the art and was especially captivated by this photo. She was so happy to see the face of another beauty that didn't quite look like everyone else. Tonight I got to meet the photographer and the woman that brought us together. Dana saw an interview with the image of Sophia in front of Ruben Natal-San Miguel's art, so she reached out to me to let me know that Ruben saw the interview and was moved. More recently, Dana said that Ruben Natal-San Miguel was coming to Charlotte for the first time and that we should all get together. I said yes, and at the time, didn’t realize it was on the six month anniversary of Sophia’s death. Though this morning was really difficult, I knew that I must keep my plans because it felt like Sophia set this all up. I’m so glad I did. I got to connect with two amazing souls on so many meaningful and real levels. This is what feeds my soul. Dana so generously gave me her photograph. It’s a piece of art and memory that I’ll treasure forever. Thank you, Sophia, for continuing to guide me and connect me to others through your impact, and thank you, Ruben, for your beautiful art. #SweetSophia #ChildLoss #Grief #NormalizeFacialDifferences

My life and posts aren’t black or white. They are all the colors in between. I share ever-changing moments in my life. If something I share is sad, it doesn’t mean I’m stuck there. I could’ve had good moments throughout the day, or I could be sharing something I've written or felt weeks earlier or something from my past(there are 38 yrs of it). Social media posts are very brief snapshots in time. You don’t see the before, after, or the in-between, and there is a lot of before, after, and in between. I hope you realize that. I also hope you know that when I write about my emotions, I do it to heal myself and when I share it, I do it to liberate myself, help others, create community, release it, move forward, and so others feel less alone, including myself. I share to be a part of a positive movement of people that work to erase outdated stigmas surrounding mental health, grief, child loss, disabilities, and facial differences. I share to normalize it. Truthtellers, storytellers, writers, and advocates changed my life for the better due to their willingness to share their experiences and their truths. If we all remained silent, nothing would change, no one would move forward, and we’d all feel alone. I hid most of my life. I worried about other's judgments, but now I say f**k that! I’m going to be me out in the open, and you know what? My life changed for the better because of it. Within three years of being open and sharing my truth, I made changes in this world, I’ve grown, I’ve connected to a huge community of loving people, and most importantly, writing and sharing are cathartic. It also cuts the bs out, and I get to connect with others who want to live beyond the surface, and that is a damn gift. If you believe grief has a timetable, if you believe sharing emotion and life experiences is bad, if you like to live on the surface, if emotions make you uncomfortable, if you’re superficial, or you find yourself judging others for living their life truthfully, openly and honestly then I am not for you and you are not for me and that is A-O(f**king)K. Big love to my supporters & thanks for sharing your truths with me. It is sacred to me. #Grief #ChildLoss #TruthTellers #MentalHealth